By Brig RPS Kahlon, VSM (Retd)

A massive 135-145 million acre feet (MAF) of water flows from India to Pakistan via the Indus, Jhelum and Chenab rivers every year. Contrast this with the fact that Punjab, Haryana, UP, Rajasthan and Delhi are already facing an escalating water deficit. The low ground water levels coupled with growing population demands calls for urgent reliable, consistent water supply.

The Indus Water Treaty (IWT) was formalised in 1960. The conditions have altered considerably since. Global warming negatively impacts the availability of water in the glacier fed (85 per cent of the total outflow) in the Indus River valley basin. Apart from the bludgeoning population which has to be provided with drinking water, there is an increasing requirement for irrigation, to ensure food security of the nation. There is a legitimate need for India to seek a larger proportion of the 16 per cent water that is currently apportioned to it by the 65-year-old treaty. India is justified in its call to re-negotiate the treaty with Pakistan, which has been hanging fire since 2023, when the issue was last flagged formally by India.

Within the constraining parameters of the IWT, India already utilises 95 per cent of the water flow of the three eastern rivers of Ravi, Beas and Sutlej. The on-going construction of the Shahpur Kandi Project, Ujh Multipurpose Project and the second Ravi Beas Link below Ujh, will ensure that India exploits the remaining 5 per cent, too, for its irrigation and water supply needs. On March 1, 2025, India officially stopped the flow of Ravi River into Pakistan after 45 years.

Also read: Unravelling the why and what of the Indus Water Treaty

The bone of contention between the two countries, however, remains the exploitation of the western rivers of Indus, Jhelum and Chenab. As per the limiting provisions of IWT, India can use these rivers’ water to irrigate 701,000 acres with water storage not exceeding 1.54 billion m3 and new storage works with hydroelectric power plants with storage not exceeding 2.0 billion m3 and nominal flood storage capacity of 0.93 billion m3. Pakistan has consistently used IWT’s dispute provisions to block India’s efforts to optimise on this provision. Legitimate hydroelectric and irrigation projects have been inordinately delayed and obstructed by them.

The IWT allows India to build “run-of-river” hydroelectric projects on the western rivers. Pakistan disputes the design and execution of these projects repeatedly. From Wullar Barrage to Kishanganga, the disagreements ranged from the placement of gates to the size of reservoirs and the interpretation of design parameters. There were restrictions imposed on flushing and refilling these reservoirs which have resulted in excessive silting.

The Pakistan fear is that a storage capacity on these rivers would allow the Indians to control the flow of the water in spite of the mutual monitoring mechanism that exist. More the storage capacity, higher is the Pakistan vulnerability downstream. That is a fact, which can be a big stick to beat Pakistan with in the immediate future, when the IWT is in abeyance.

Pakistan has, over the last seven decades of its existence, proved to be an incorrigible and unreliable neighbour, as far as honouring bilateral agreements and treaties is concerned. Be it the Indus Water Treaty, the Shimla Agreement, or something as routine as the Ceasefire Agreement on the LC. It has been incumbent on India to make bilateral agreements work, while it is the proven nature of Pakistan to violate them time and again for its own benefit. The suspension of the IWT by India in response to the Pahalgam massacre is an apt response to give Pakistan a taste of its own medicine, where it hurts her where she is the most vulnerable.

Suspending the treaty allows India to fast-track dam construction on the western rivers. In Jammu and Kashmir’s Chenab Valley alone, seven major dams are underway: Pakal Dul (1,000 MW), Kwar (540 MW), Kiru (624 MW), Kirthai I and II (1,320 MW), Bursar (800 MW), and Ratle (930 MW). Collectively, they aim to generate over 5,000 MW of hydroelectric power. The water stored, denied and which can be released at will as a consequence, is the icing on the cake.

In what some are calling an eco-strategic chokehold, India is now free to flush and refill reservoirs not during the monsoon, but in the dry season - from October to February - thus disrupting Pakistan’s sowing season. Major Kharif crops such as cotton, maize, sugarcane, pulses, and oilseeds are expected to be significantly affected, plunging the region into food insecurity.

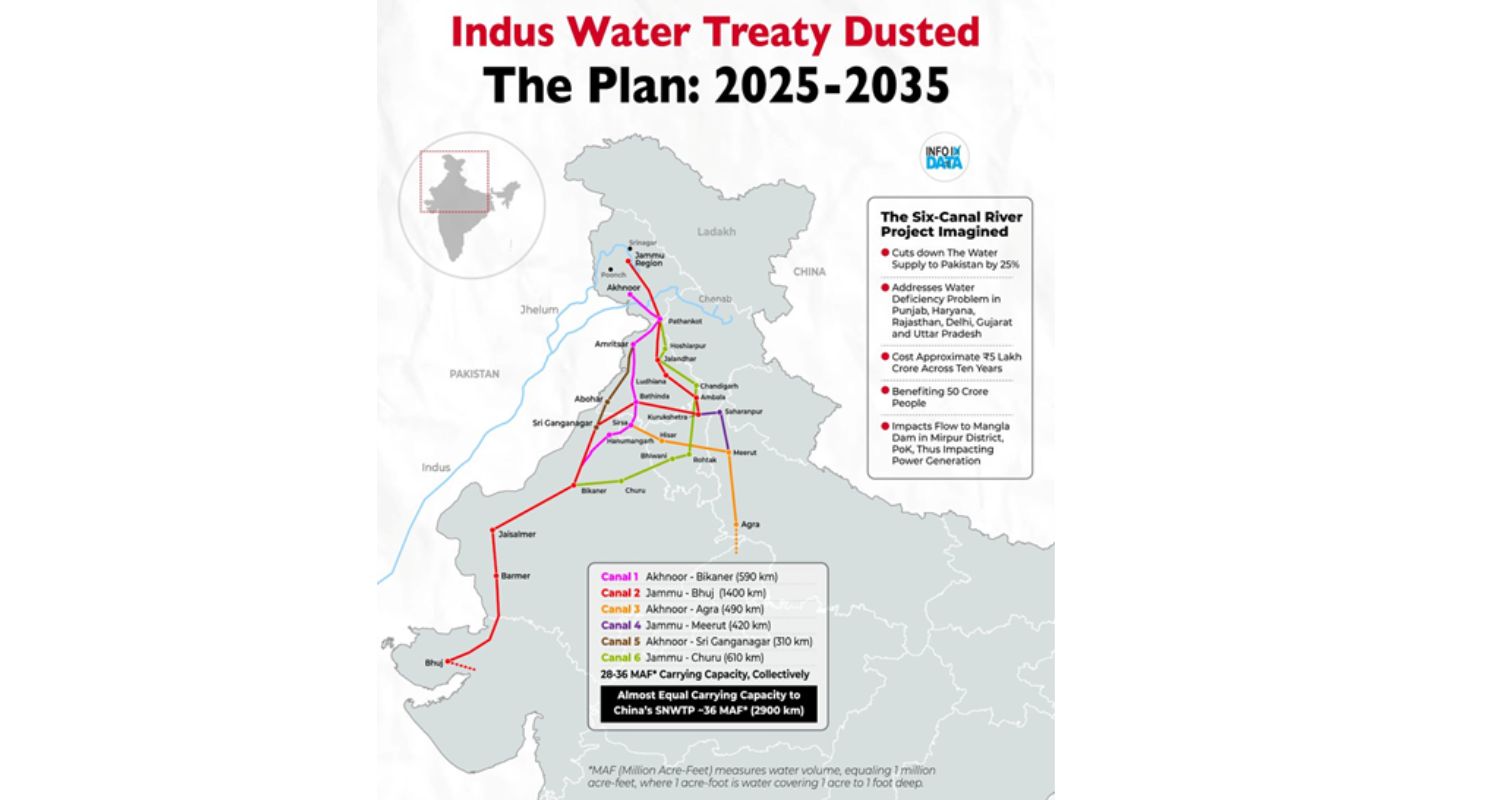

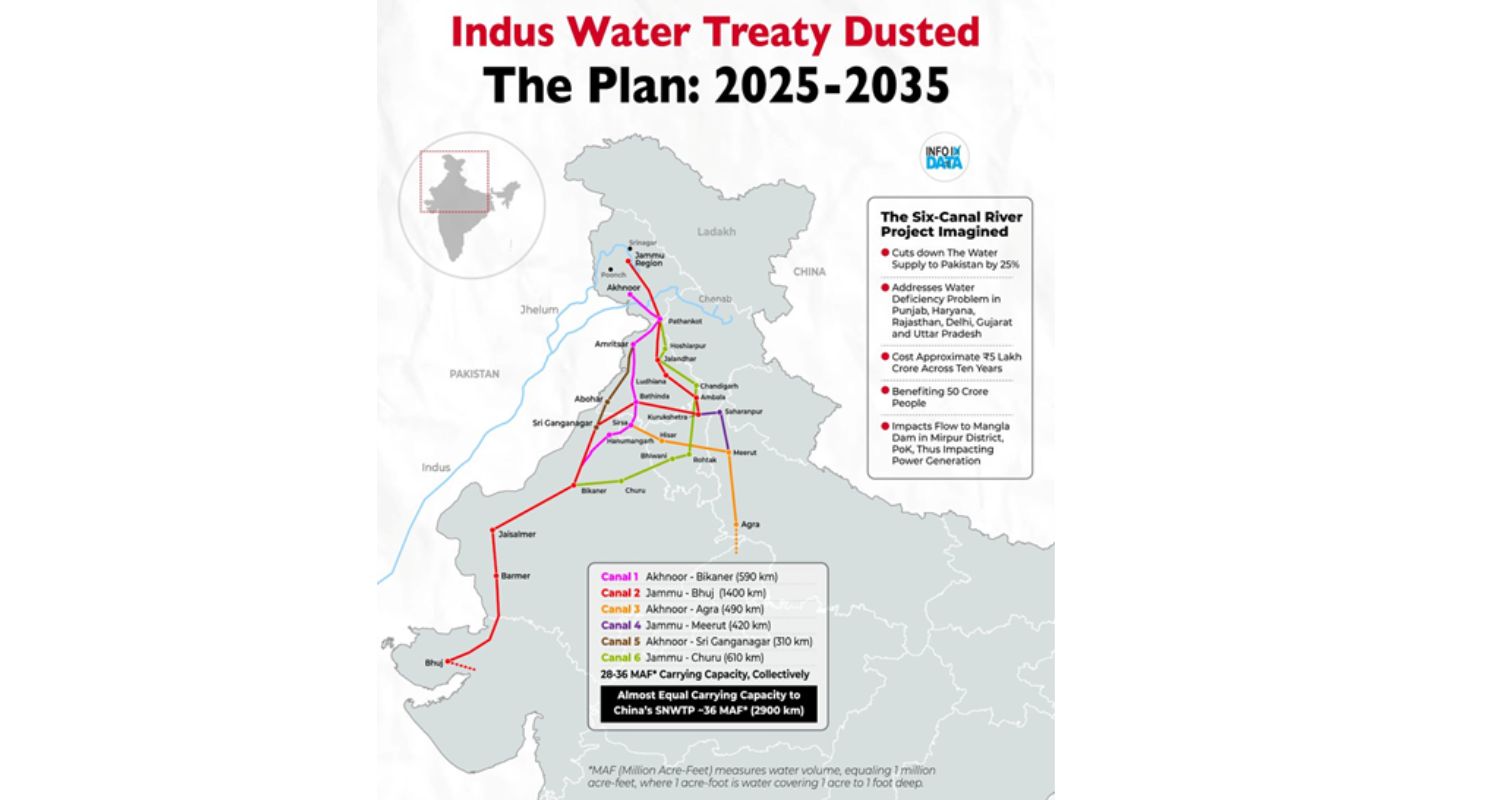

Freed from the restraints of the IWT, India can now consider harnessing and supplementing its existing river and canal networks to redirect water from the Jhelum and Chenab rivers, to channel a possible 28-36 MAF of water into the water-scarce regions, including Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Delhi, and Gujarat.

The concept is similar to China’s South-North Water Transfer Project, which successfully moves water from the south to the north over 2,900 km. Conceptually, it would mean constructing six canals that would span 3,000 km across the northern plains, supplementing the existing canal network. This system would not only address the immediate water crisis but also fuel economic growth and increase agricultural productivity in these regions.

Currently, Pakistan relies heavily on the waters of Jhelum and Chenab. Reduction in the water flow would severely affect their agriculture and hydroelectric production.

In the larger picture, India’s priority is to ensure the security, well-being and economic development of the Indian citizens. By reorienting the terms and conditions of the IWT as estimated above, India can not only improve its own water security, but also create leverages to coerce Pakistan to her bidding. Water and blood both cannot flow. For water to flow, blood has to stop. But water should flow as India desires, and that would kill two birds with one stone.