Uttarakhand has taken another step in fusing ancient knowledge with modern conservation by creating a “Mahabharata Vatika” in Haldwani, an ethnobotanical garden spanning an acre.

This unique endeavour showcases 37 plant species mentioned in the Mahabharata, with the aim of connecting ecological heritage to contemporary environmental concerns.

The initiative follows the establishment of the “Ramayana Vatika” earlier this year, where 70 plant species mentioned in Valmiki’s epic were grown.

The Mahabharata Vatika serves as a living repository of wisdom, displaying plants such as Peepal (Ficus religiosa), Bargad (Ficus benghalensis), Harsringar (Nyctanthes arbor-tristis), and Shami (Prosopis cineraria), among others.

Chief Conservator of Forests, Sanjeev Chaturvedi, spearheaded this ambitious project.

“The Mahabharata Vatika shows us the importance of forests as per the great epic. It highlights the ecological and spiritual wisdom conveyed through its hymns,” he said.

The Mahabharata, with its 100,000 shlokas, offers profound insights into the environment and its preservation.

According to Chaturvedi, the Vana Parva of the epic reflects on the role of forests, urging the planting of trees and the protection of wildlife.

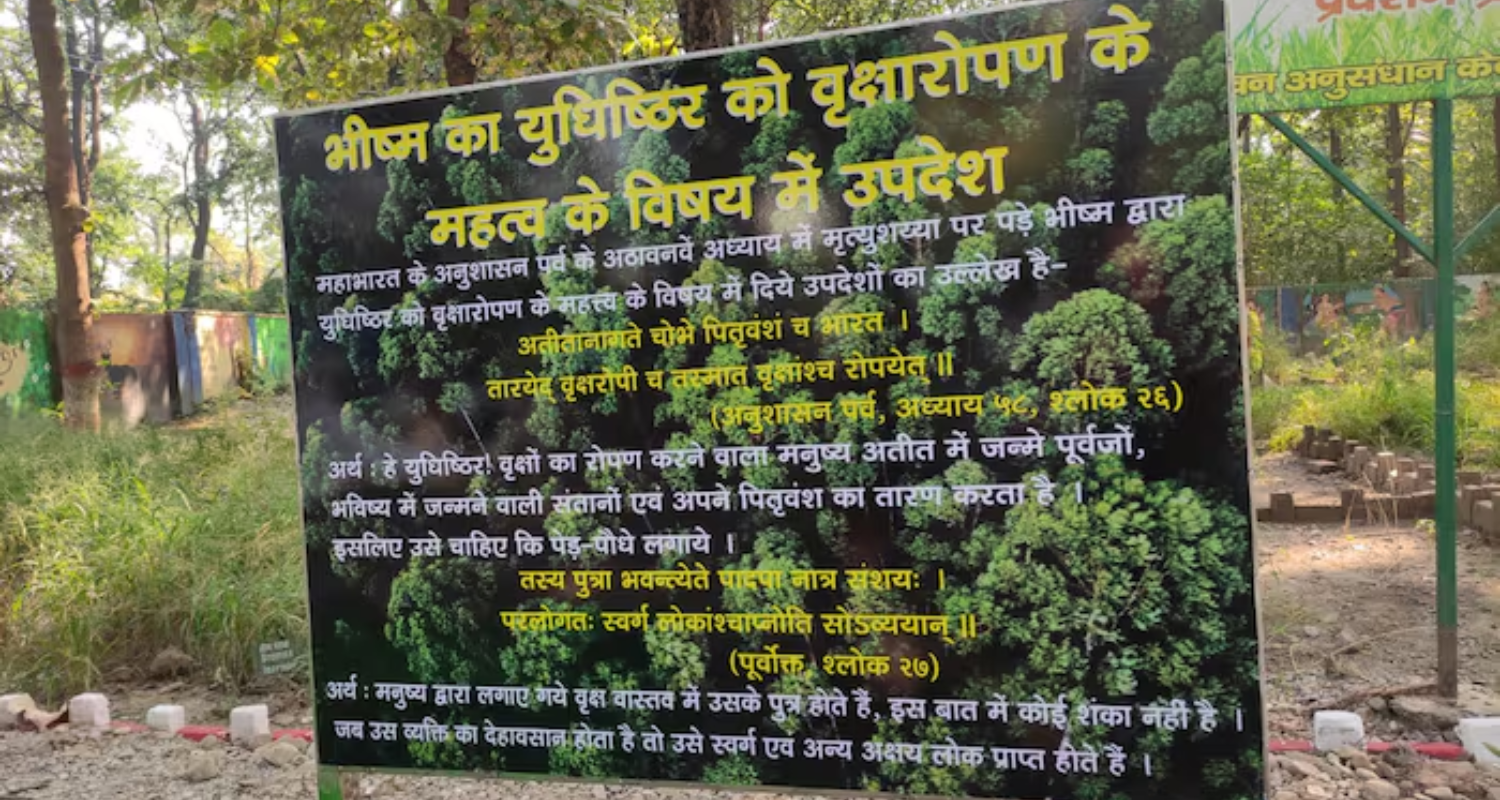

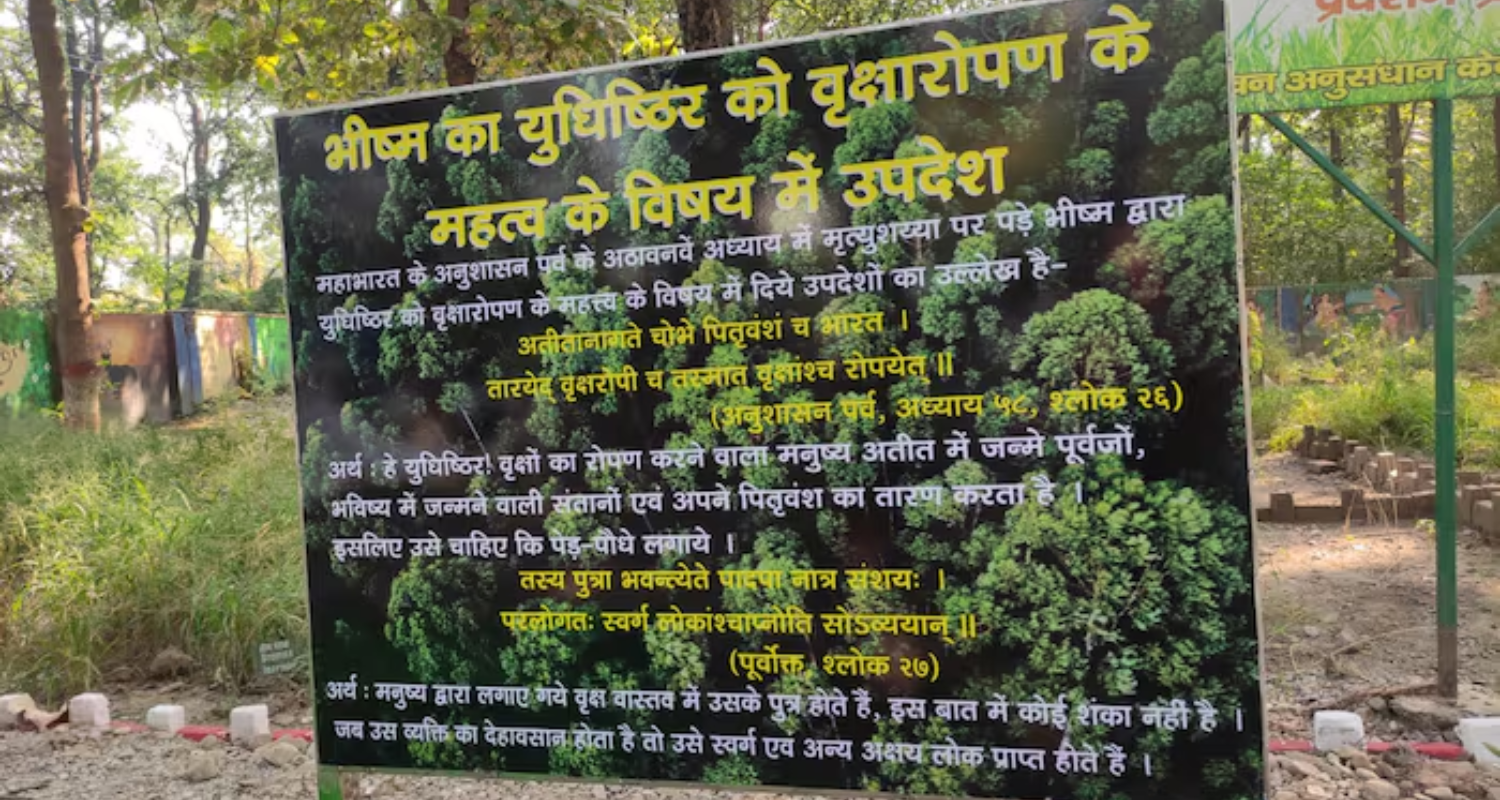

He cited Bhishma Pitamah’s teachings to Yudhishthira in the Anushasana Parva: “The one who plants trees uplifts both the ancestors and the descendants along with their lineage. Therefore, one must plant trees.”

The garden encapsulates these teachings, blending ancient cultural practices with ecological awareness. From the Dhak tree (Butea monosperma) to the Shami, each plant tells a tale.

The Shami, for instance, holds a special place in the Mahabharata as the site where the Pandavas hid their weapons during exile, later retrieving them to engage in the Kurukshetra war.

The Shami is still revered today, with its leaves exchanged during Vijayadashami celebrations as symbols of prosperity.

Chaturvedi elaborated on the ecological lessons embedded in the Mahabharata, such as the symbiotic relationship between tigers and forests.

Referring to the Udyoga Parva, he noted, “Without forests, tigers are killed, and without tigers, forests are destroyed. This profound wisdom highlights the mutual dependence between tigers and forests, a concept central to modern conservation efforts.”

The garden also illustrates the epic’s early understanding of natural processes, such as photosynthesis.

“The role of light in sustaining plant life is mentioned, reflecting an ancient grasp of ecological interdependence,” Chaturvedi added.

The creation of this Vatika complements the Ramayana Vatika, which features flora associated with Lord Rama.

Together, these gardens aim to blend mythology, history, and environmental consciousness, offering a serene yet educative experience.

“The Mahabharata Vatika,” Chaturvedi remarked, “demonstrates the richness of our ancient texts in addressing timeless environmental concerns and provides inspiration for current conservation practices.”