In the heart of West Bengal, Purulia’s rugged Ayodhya Hills, where development has rarely set foot and villages remain wrapped in obscurity, a quiet revolution is taking place, led not by a politician or a celebrity, but by a tribal housewife named Malati Murmu.

Once just another daughter-in-law in the remote tribal hamlet of Jiling Seren, today Malati is a beacon of hope, determination, and transformation. For five years now, she has been tirelessly running a free school out of sheer willpower, aiming to pull her community out of the shadows of illiteracy and into the light of knowledge.

The name Jiling Seren seldom makes it to maps. Nestled deep within the hills, about 25 km from the Ayodhya hilltop, it’s a village known more for its isolation than its potential. In 2019, when Malati arrived here as a new bride, she was struck by something deeply unsettling: the near absence of education.

Children wandered aimlessly. Teenagers toiled in the forests or stayed back home, education never more than a passing thought. The local school, far from being a lifeline, had become a lost cause, especially after the 2020 COVID-19 lockdown. Online classes meant nothing in households without electricity, let alone smartphones.

But for Malati, who had completed her higher secondary education, this was unacceptable. She knew the cost of illiteracy and what it robs from an entire generation. And so, quietly but firmly, she began her mission, a classroom inside her own home.

Initially, Malati’s mission was met with scepticism, resistance and even ridicule. Parents scoffed: “What will happen with education?” Her own family discouraged her. But armed with conviction, Malati went door to door, urging families to send their children. With her baby on one arm and chalk in the other, she taught them herself.

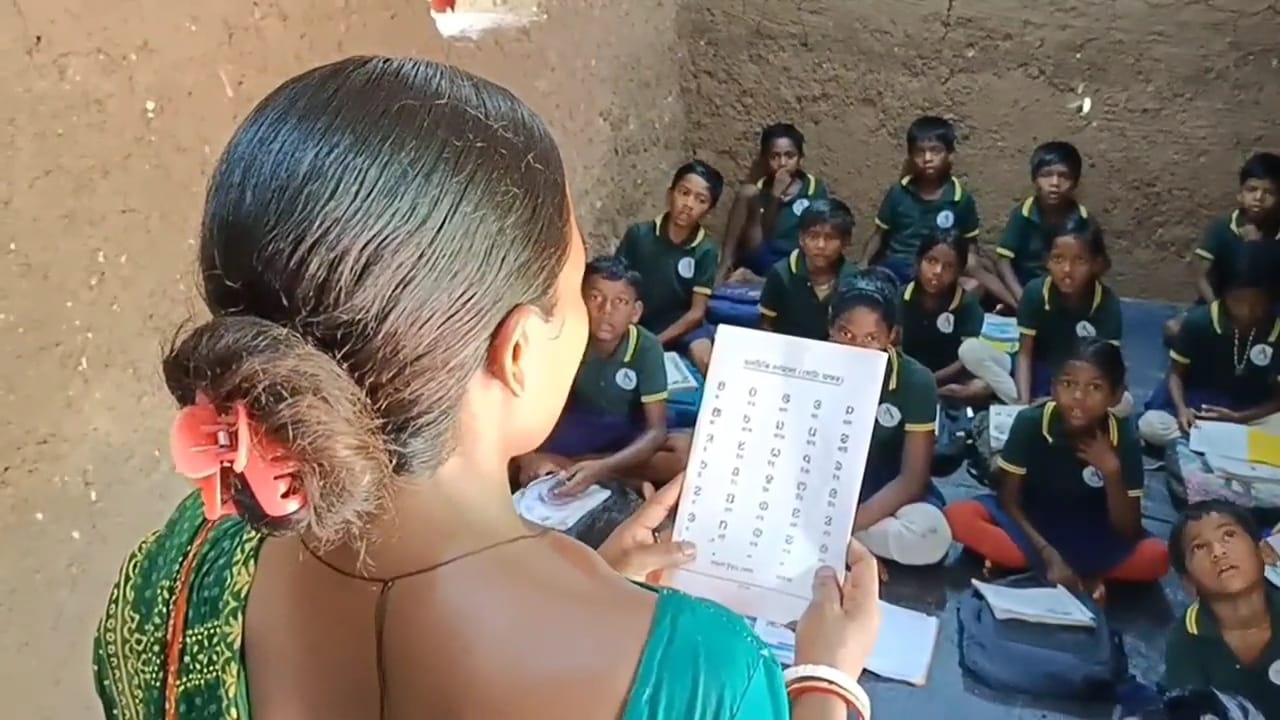

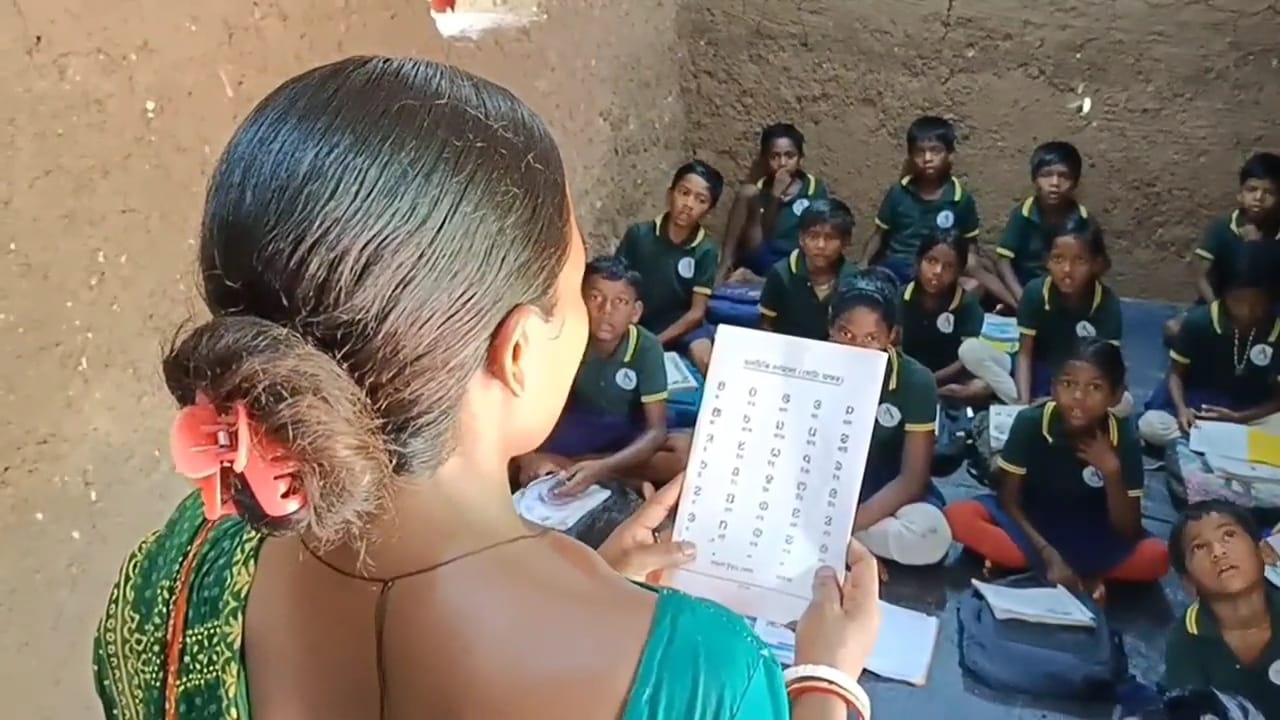

She started with just a handful of children, reluctant and uncertain. But her teaching, rooted in love, simplicity and cultural sensitivity, began to stir something within the community. Slowly, parents started believing. Children returned, some even school dropouts who had lost touch during the lockdown.

Also read: In a first, Santhal girl from Assam earns MBBS degree

Malati’s husband, Banka Murmu, once sceptical himself, became her staunchest supporter.

“How will this village grow if there is no education?” Banka, a daily wage earner, now says, standing beside her like a quiet pillar of strength. Together, with the help of villagers, they built a structure, a two-room tiled house with no benches, just dreams and determination.

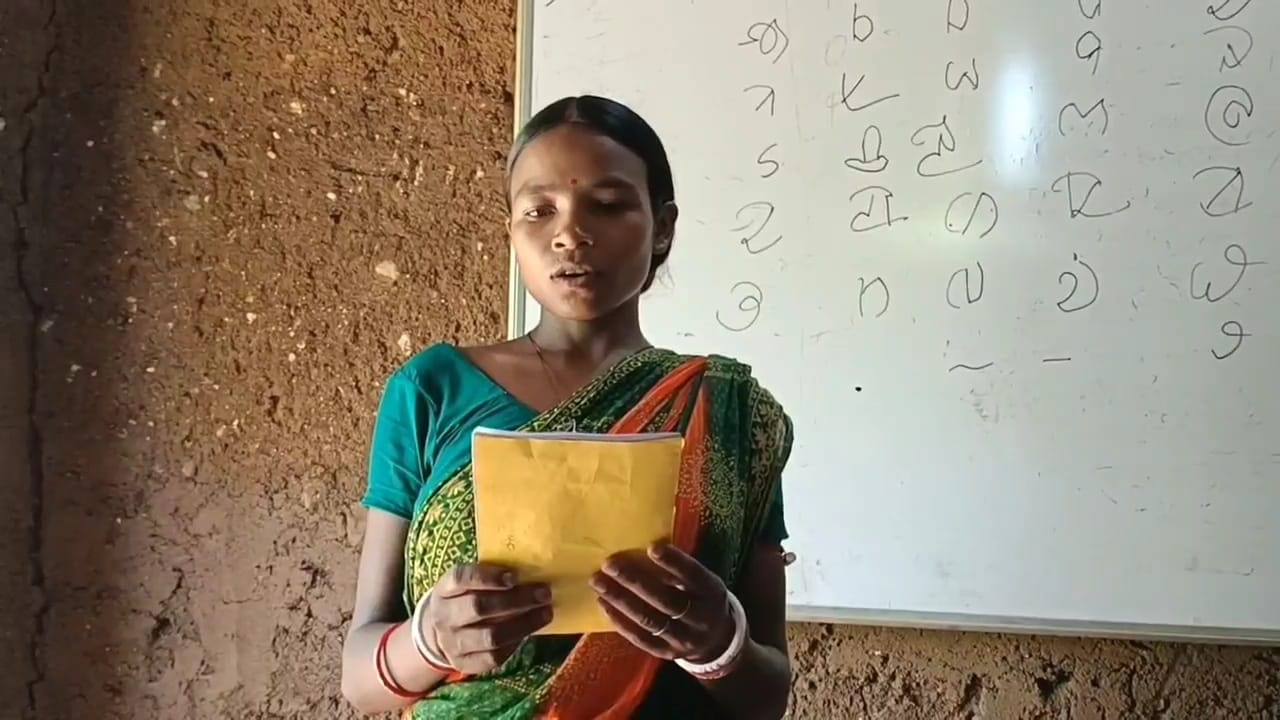

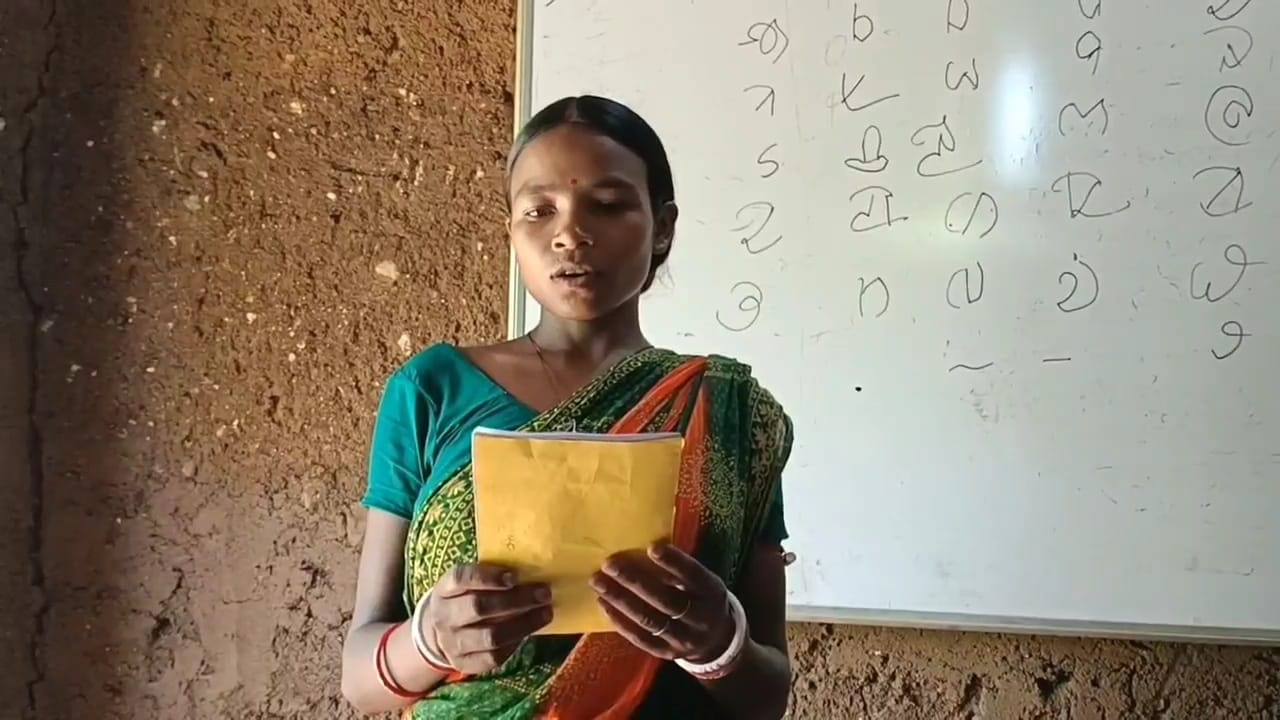

Today, Malati teaches 45 students from Class I to IV in Santali, Bengali, and English. Her curriculum isn’t bound by textbooks. She fights superstition with science, uses stories to spark imagination, and blends tradition with modernity. She’s not just a teacher, she is a changemaker.

Malati’s youngest child is only two months old. Yet, even on the most chaotic days, you’ll find her conducting classes with her infant gently cradled in her arms. Her students sit cross-legged on the mud floor, their eyes bright, their minds curious.

“Earlier, no one cared if their child studied or not. Now, they ask me what books to buy,” Malati says with a smile that hides years of struggle, adding, “I want children from nearby villages to come too. This light of education must spread.”

Though many NGOs showed early interest, they eventually backed away, citing logistical constraints. Yet, word of Malati’s school has begun to travel.

Recently, noted educationist and social worker Chandrashekhar Kundu, known for his “Boithai-Hoichai” educational initiatives in tribal belts, visited Jiling Seren. Moved by Malati’s work, he promised long-term support.

“There’s no reason children in this village shouldn’t experience the same kind of education happening in smart classrooms elsewhere,” Kundu said, adding, “We will work on upgrading her centre, smart classes, better infrastructure, proper teaching tools. Malati has laid the foundation. It’s our job now to strengthen it.”

The very villagers who once doubted her now sing her praises. Mothers like Minati Soren and Sunita Mandira say their children were lost until Malati stepped in. “The school was shut. The children sat idle. Malati took charge. Now they love learning,” says Minati.

From one forgotten corner of Purulia, a tribal housewife has rewritten the narrative of what it means to bring change. With no salary, no institutional backing and no stage to stand on, Malati has become the living embodiment of the ‘Tej’, the burning light Bengali poet Debabrata Singh once wrote about in his poetry.

And just like that, in a village where the sun once set too early on young dreams, a new dawn has begun.