Trending:

Patachitra: The fading scrolls of Bengal’s living canvas

A Patachitra painting is a slow miracle. The canvas is made from old cotton saris soaked in a paste of chalk and tamarind seed, then polished smooth with a conch shell.News Arena Network - Kolkata - UPDATED: October 17, 2025, 03:37 PM - 2 min read

The Patuas use brushes made of fine bamboo sticks wrapped in cotton.

In the quiet, sunlit corners of Rampurhat in West Bengal, a man bends over a piece of cloth stretched taut across a wooden frame. With steady hands and a brush carved from bamboo, he paints—not just with colour, but with memory. Each stroke is deliberate, every hue ancestral. His name is Kalam Patua, one of the last few living masters of Bengal’s Kalighat Patachitra—an art form that once sang the stories of gods and men, and now struggles to be heard amid the static of modernity.

By day, Kalam serves as a postmaster; by night, he resurrects Bengal’s 300-year-old legacy. His world may be small—the walls of a modest home, a few brushes, jars of pigment, and time—yet his imagination stretches across centuries. “I grew up making patachitra scrolls that told folktales and mythologies,” he says. “But Kalighat painting is different. It mirrors society—its hypocrisy, its humour, its pain.”

Once, these paintings were the voice of Bengal’s streets—bold, biting and unafraid to mock the powerful. Today, they whisper their survival story.

A scroll that sang

The word Patachitra comes from Sanskrit—patta, meaning cloth and chitra, meaning picture—literally translating to “painting on cloth.” The art form, believed to have originated in 5th-century BCE Odisha before flowing into Bengal, was more than visual beauty; it was a narrative tradition. The artists, called Patuas, were both painters and storytellers. As they unfurled long scrolls painted with divine epics or village tales, they sang pater gaan—folk songs that brought the stories to life.

In Odisha, Pattachitra found its sanctum in the Jagannath temple of Puri, its themes rooted in the divine incarnations of Lord Vishnu. But in Bengal, the art took a different turn—away from temples and toward the streets. Kalighat Patachitra, born near Kolkata’s Kalighat temple in the mid-19th century, chronicled the rise of the urban middle class, the vanity of the nouveau riche babus and the social ironies of colonial India. The paintings evolved from devotion to satire and the Patuas became Bengal’s first cartoonists—their scrolls, the subcontinent’s earliest social commentary.

Kalam Patua: Keeper of the lost irony

Born into a lineage of storytellers, Kalam learned to paint from his uncle, Baidyanath Patua, at the age of 10. His artistic journey began with traditional patachitra scrolls—depictions of Durga’s battles, Krishna’s love and moral parables from village lore. But as the world around him changed, so did his brush.

“I realised there were only a handful of artists left who practised this style,” he recalls. “I wanted to bring it back—but make it speak to today’s world.”

He did. In Kalam’s work, mythology meets modernity. His paintings show a man watching the 9/11 attacks on TV, a woman staring at a mannequin dressed in Western fashion, a politician raising his hand before a silent crowd. His humour is subtle, his colours restrained—each piece both a question and a confession.

Despite international recognition—his paintings have been displayed at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the National Museum in Liverpool and the Museum of Civilisation in Canada—Kalam remains deeply rooted in Bengal. “I am still that boy from Rampurhat,” he says with quiet humility, adding, “My art is my way of speaking to people, not to the world.”

The dying brushstrokes

In the narrow lanes of West Midnapore, a few families still cling to the art their ancestors passed down—the patachitra scroll painters of Naya village, the Patuas. Here, art is not a hobby; it’s a way of living, breathing and remembering.

But the air of nostalgia carries a note of despair. The younger generation no longer wishes to inherit the brush. “A single patachitra can take months,” says artisan Salma Biwi, her hands stained with indigo. “We work for days, and still, there are no buyers.”

Her husband, Sheik Shuvan, adds, “We are Patuas—painters and singers. Our art was meant to travel from village to village. But now, who listens to stories anymore?”

Also read: Chandannagar—the glowing heartbeat of Bengal

With modernisation and migration, the scrolls are gathering dust. Digital prints, mass-produced wall décor and economic instability have forced many artists to abandon their craft. “People buy cheap factory art. They don’t understand the soul of handmade stories,” says Salma bitterly.

Yet, not all is lost. Some artists have tried to adapt—bringing Patachitra into the contemporary dialogue. Ahead of the 2021 Bengal Assembly elections, artisans from West Midnapore began painting political scenes—Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee addressing rallies, helicopters soaring, crowds cheering. “Politics is the new mythology,” laughs Shuvan. “We just painted what we saw.”

These modern scrolls became local sensations—a rare fusion of heritage and headlines. But while creativity blooms, sustenance still lags. “The art has evolved,” says cultural curator Surajit Nayak, founder of Prattya.com, an online platform that organised a Patachitra fair at Rabindra Sarobar, Kolkata. “But unless the artists earn enough to live, the tradition will not survive.”

The anatomy of a scroll

A Patachitra painting is a slow miracle. The canvas is made from old cotton saris soaked in a paste of chalk and tamarind seed, then polished smooth with a conch shell. The pigments—never synthetic—come from earth and plant: white from ground conch, black from lamp soot, red from cinnabar, blue from indigo, yellow from turmeric and haritala (arsenic sulphide).

The Patuas use brushes made of fine bamboo sticks wrapped in cotton. There is no pre-sketching—only instinct, rhythm and inherited discipline. Each scroll, often up to 15 feet long, unfolds like a storybook—each frame a verse in visual poetry.

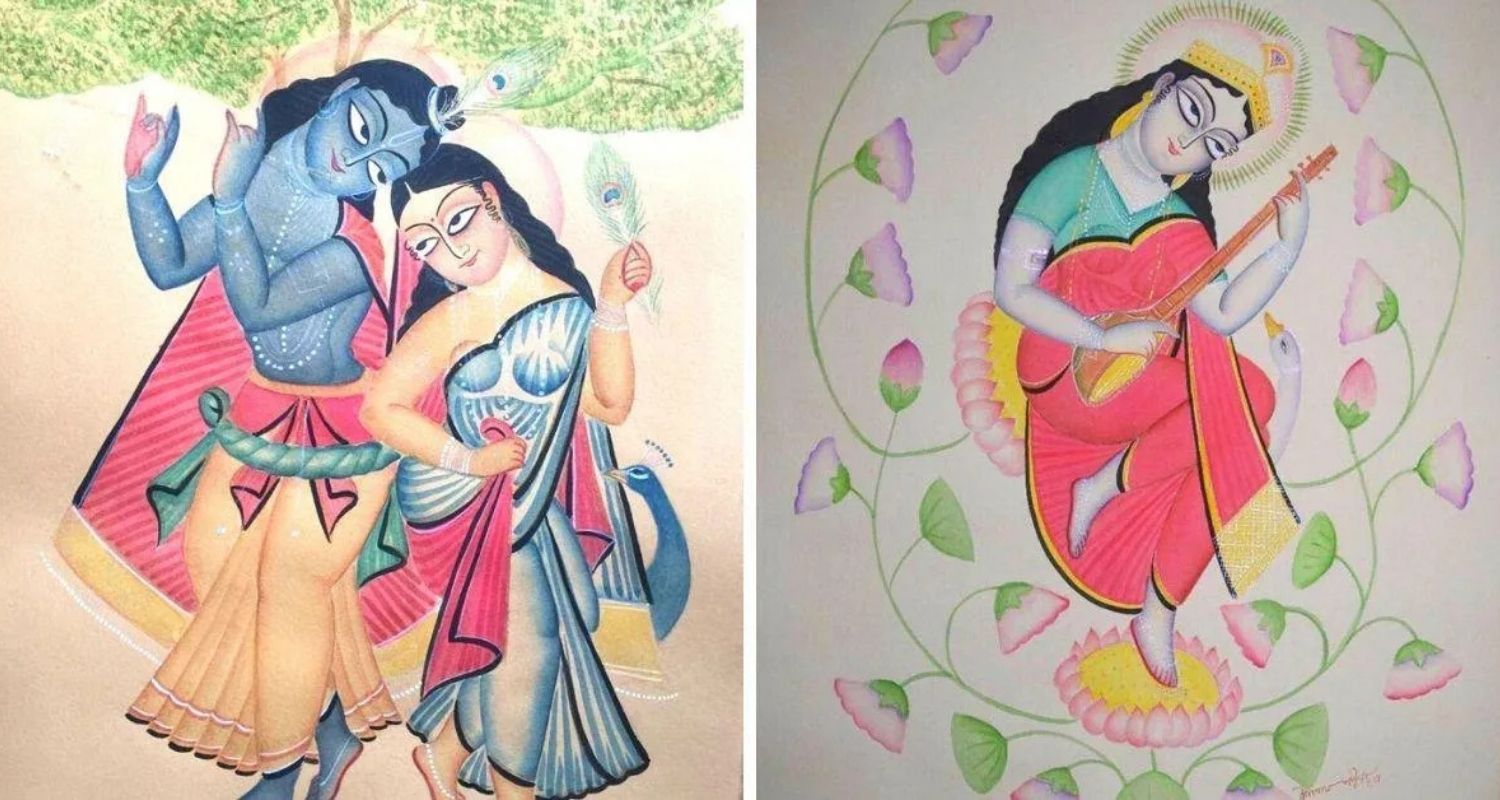

Traditionally, the subjects were divine: Durga slaying Mahishasura, Krishna playing his flute, Rama’s exile, Chandi’s triumph. But over centuries, themes expanded—to love, betrayal, social reform, even gossip. The Kalighat Patua painters of colonial Kolkata were among the first to paint not gods but humans—the flirtatious babu, the coquettish bibi, the greedy priest, the corrupt officer. Their humour was their rebellion.

A tradition between faiths

What makes Bengal’s Patachitra truly remarkable is not just its art, but its soul. The Patuas belong largely to the Muslim community, yet they paint Hindu deities with reverence. They sing of Durga, Krishna and Kali while practising Islamic customs at home. “For us, art is our religion,” says Kalam simply.

They call themselves the “children of Vishwakarma”—the divine craftsman—and live by the belief that creativity transcends faith. This quiet syncretism, a coexistence of devotion and freedom, is what makes Patachitra a living testament to Bengal’s plural heritage.

From scroll to screen

Patachitra, in recent years, has found new life beyond galleries and scrolls—on textiles, jewellery, murals and even cinema. Its bold lines and vivid motifs have inspired fashion designers and animators alike. Filmmakers, especially in Bengal, have used Patachitra-inspired visuals in title sequences and animations to root their stories in cultural authenticity.

“The Patachitra scroll is the original storyboard. It’s visual storytelling at its purest. Cinema is simply its modern echo,” says film historian Anindita Ghosh.

Yet, while global audiences marvel at its aesthetic, the lives of its creators remain precarious. Most artisans earn less than Rs 10,000 a month, relying on seasonal fairs and exhibitions. Without institutional support, many fear that within a generation, the scrolls will be silent forever.

A flickering lamp

In the age of smartphones and digital art, Patachitra stands as a relic—slow, meditative and profoundly human. Each painting is an act of patience, a prayer for continuity.

As dusk falls over Rampurhat, Kalam Patua cleans his brushes, the air thick with the smell of pigment and tamarind. Tomorrow, he will sort mail by day and return to his scrolls by night. “Maybe this art will die with us,” he says, his eyes fixed on a half-finished painting of a woman holding a mobile phone before a mirror. “But even if no one remembers my name, I hope they remember that once, colours could sing.”

Patachitra is more than an art form—it is the painted memory of India’s collective consciousness. It has witnessed the shift from oral tradition to digital screens, from village fairs to museum walls. Its decline is not just the fading of a style, but the dimming of a philosophy — that art is for everyone, that stories belong to all.

And perhaps that is what makes every brushstroke precious. For as long as there is one Patua left—one storyteller who still dares to paint the world in his colours—Bengal’s scrolls will continue to sing, softly, defiantly, against the noise of forgetting.

By Pranab Mondal