Trending:

Kochi-Muziris Biennale: A university of art

This year the biennale is larger and more ambitious compared to its previous editions. It is spread across Fort Kochi, Mattancherry, Willington Island and Ernakulam.News Arena Network - Chandigarh - UPDATED: January 11, 2026, 01:30 PM - 2 min read

There are surprises too. Security is a new addition.

In times, when visual literacy is shaped by selfies and reels, most art events tend to become exclusive. Because the vocabulary of visual art is getting more and more complex to comprehend. Leading, at times, to the obscure.

The advantage of art events like a biennale is—it offers a diversity of idioms of the visual language from different cultures of the world.

The sixth edition of KMB (Kochi-Muziris Biennale) at Kochi, Kerala, offers a lot more. It introduces an art lover to the new and emerging art practices—adopted globally. This year, for example, globally renowned established and emerging artists and collectives—Marina Abramovic, Abrahim Mahama, Nari Ward, Shiraz Bayjoo, Maria Hassabi, Otobong Nkanga and Geiv Patel’s works and performances are part of the biennale. A retrospective exhibition of Gulammohammad Sheikh’s works is on display at Darbar Hall, Ernakulam.

There are surprises too. At the entrance, a security guard with a body builder’s physique was asking, “Are you an artist?” before checking my ID and letting me in Aspinwall House, one of the 22 venues of KMB 2025-26.

Security is a new addition. It felt out of place for an art event. I have been a witness to KMB’s evolution, without much security.

Why does one need bouncers at people’s biennale?

Later, in an interaction with performance artist Nikhil Chopra, curator of the sixth edition of KMB, I enquired about the need for security. “So many lives are involved, so many creative works are on display, we need to provide them a secure atmosphere to practice their art,” he emphasised. In his curatorial statement too, he stated, “…it is a place of refuge and rebellion.”

Later, KMB was forced to remove Tom Vattakuzhy’s illustrative work under pressure from Christian organisations at Kochi. It lent legitimacy to greater need for security for art shows of the scale of KMB.

From heart to heart—the world is helpless

Few works at KMB startle with mere visuals. A dramatic visual leads the viewer to a gallery of brightly illuminated, tall flowers in green and red against a dark purple backdrop. The giant pitcher plants with drooping petals hide secrets one could hear in whispers—played incessantly on an audio device. The voices seem to come from a deep space. Tall wooden boxes, hidden amidst the flowers reveal the dark secret behind the alluring flowers. As though stating things are rarely as they appear. Amidst muted sounds a message flashes in one of the boxes—from heart to heart—the world is helpless; these are excerpts from interviews with the former residents of a detention camp of the separatist organisation United Liberation Front of Asom (ULFA).

Dhiraj Rabha’s installation, based on news reports related to the ULFA members and their life in the region, is intense. It is complemented with towering wooden boxes, like watch towers—he had grown up with. The dramatically staged recapture, replays the stories from that time and space. Rabha grew up in one such camp. Adjacent room shows a burnt house and pictures of more stories from the camps of ULFA rebels from Assam. It is gloomy.

Whispers Beneath the Ashes, an allegorical film is played to complement the narrative with hope, in the adjacent space. Children journeying through a forest uproot bamboos to make a home; they meet strange creatures on the way and stop to ask “Tell us, where is the joyland! Oh dove! Tell us where it is?”

A number of installations at KMB carry the threads of insurgency and repression. This space is for free expression, without fear of repression. Yet, few works seem pretentious. Other few are jumbled with too many elements that seem to clutter and obscure the theme. There is one installation on the issue of caste. I could not have a dialogue with this work, perhaps it was my failure to read the caste connotations in several heads of a horse and a tail moving with a mechanical device.

At Coir Godown, a visually jarring installation by Panjeri Artists Union displays conceptual explorations of ‘time’. The introduction raises expectations since the timeline involves the checkered history of partition of Bengal. Too many objects and images distract. Among several other installations you see parts of the human body placed at different levels of a construction site. It places a question; if bodily construction were to be in parts—which ones would be marginalised and silenced! Which one would be worthless!

It triggers a dialogue with the viewer. The organs that watch and express would, perhaps, be the ones.

Also read: Patachitra: The fading scrolls of Bengal’s living canvas

There is a medley of historical conjunctions; symbols of the collective memories; pre and post war scenarios that look rather chaotic and overstated. Visuals of red flags with symbols of trade unions and graffiti and a lot more; the artists’ union worked for 100 days at Kochi to create this show.

The hanging sea

Like the wings of a stage, the sea green curtain-like copper plates hang from the ceiling, punctuating a rather dull space. The visual itself captivates. Sydney-based artist Kirtika Kain applies experimental printmaking processes to materials that have been used for thousands of years in rituals and ceremonies, such as tar, copper, gold and cotton. She has displayed works in tar and gold leaf as well as a series of suspended copper plates that punctuate the viewing space. Titled Chronicles, the work is witness to volatility and swathes of time that inscribe the suspended sea-green copper plates with layers of crusting, peeling patina—cotton lamp wicks dipped in tar are embedded across the plates. A familiar material thus becomes unrecognisable in altered context. Her work alters the visual space.

Birender Yadav’s art practice or rather work, is built around questions of labour and identity. The dominating presence of a sandook (tin box) and holdall, a symbol of nowhereness of the migrant labour, remind of Van Gogh’s A Pair of Shoes, symbolising life, labour and struggle. The worn-out existence carries an untiring power of survival. Each fold and scratch is an added layer of hard labour. There are aujars, the tools, the way they are hung or placed. The unwritten relevance of these details in the daily lives of labourers pulsates through the installation. The space has a hypnotic quality about it. Titled, Only the Earth Knows their Labour, the installation recreates a brick kiln, where the workers might be absent but their anonymous labour is highlighted through elements moulded in clay, from tools to folded clothes and the trunk, that holds their belonging and a bended vertebra in clay is suspended from the roof to show the form it takes after lifting heavy weights for years.

Yadav’s father and uncles worked as blacksmiths and miners in Dhanbad. His art pulsates with labour—it comes from his close observations and lived experiences.

Canvas art thrives

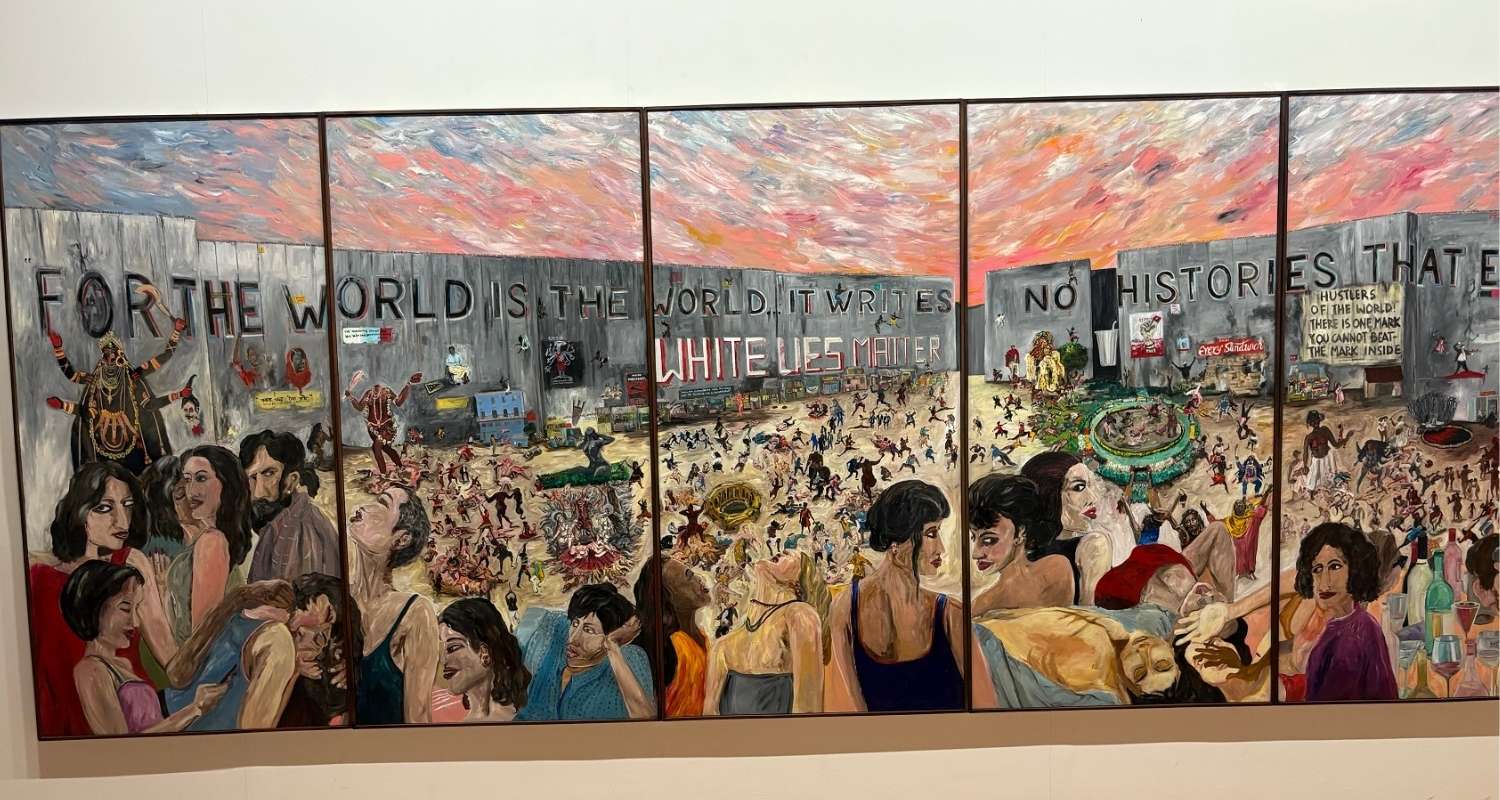

At a biennale where emerging and established art forms are juxtaposed—fluidity of mediums and genres force the viewer to look for meanings in multiple dimensions. Among many emerging practices—the familiar medium of canvas art not only survives here, it thrives.

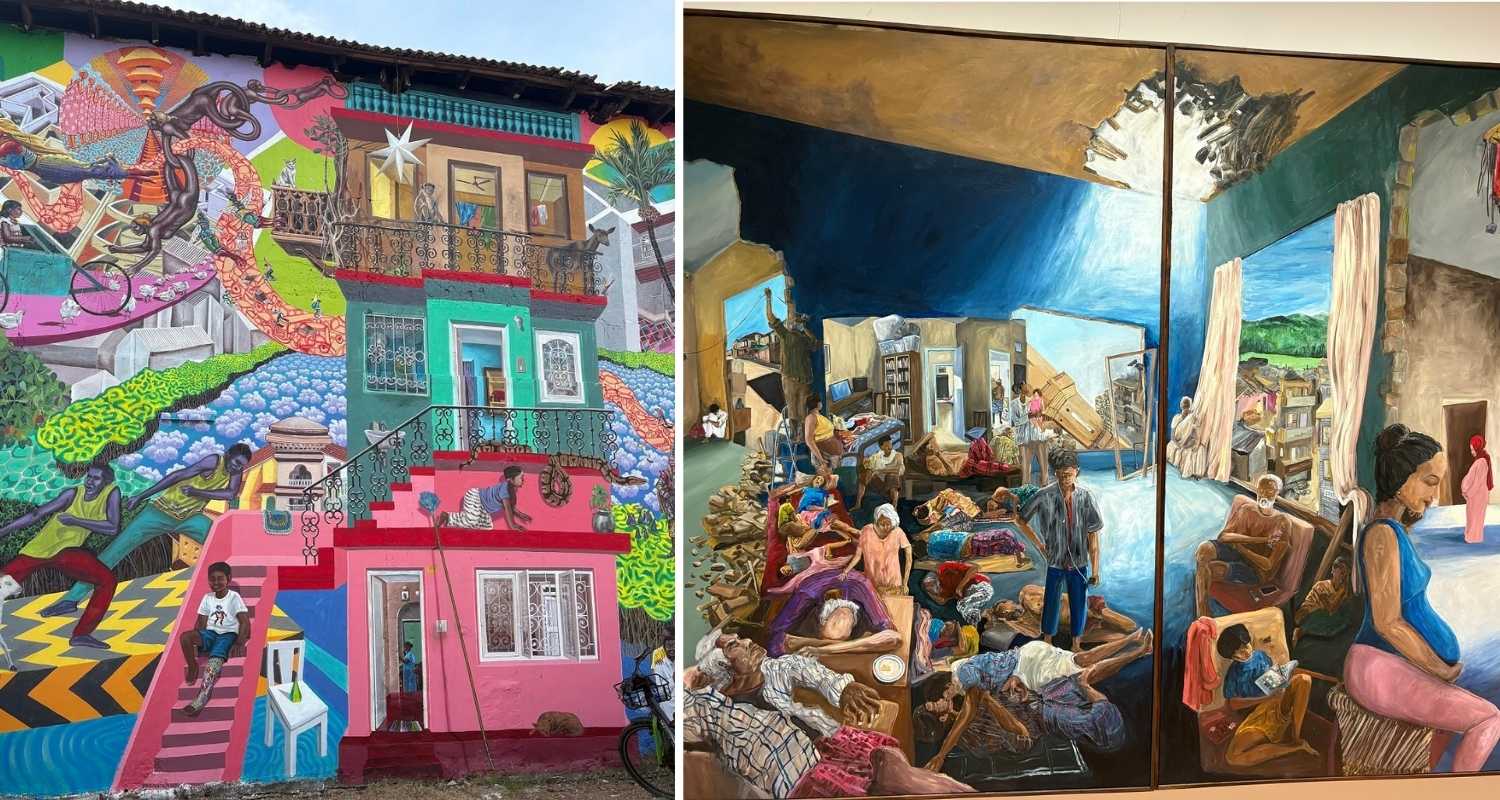

At Pepper House, four large canvases of artist Nityan Unnikrishnan create a visual architecture that is frozen in the moment—it is on the verge of toppling the frame—at the same time. The acrylics on canvas works offer multiple views of figures, objects, places and events—within this he creates a counter-space—a counter-site. All this is sculpted around our world—a phantasmagorical world emerging from our reality. Details are precise in these spaces yet always, askew. As though one is trapped in a nightmare.

Also read: A heritage village where art evolved as ‘sewa’

Through the imagery, in All of Us, Hymns of the Drowning, Sing you to Sleep and We’ve got Tonight, people seem to be in the danger of being sucked into another universe. The gravitational pull of the time contorts bodies into strange postures; multiple perspectival juxtapositions morph the figures, they grow and shrink right next to each other.

Unnikrishnan was trained in ceramics at NID, Ahmedabad. His move to painting was gradual. The branching off in painting from conventional visual representation; by adding a surreal visual vernacular, pushes the viewer into mindscapes as well as into emotive states.

Another artist from Kerala, Smitha M Babu’s almost lyrical works stun for using one of the most challenging mediums—watercolour—with a technique that lends an opaqueness to her works. She breaks the transparency conventionally associated with watercolours by layering pigments to achieve an opaque density.

About 30 of her small works, in varying shapes mesmerise viewers at Pepper House. Titled Pakkalam, a Malayalam word for the weaving workshop, the paintings-- conceived as an archive of personal memories and a sensorial documentation of Kollam’s coir making communities, are supported with her well-choreographed theatrical performance on the theme. Smitha is a trained theatre artist, with over two decades of experience in performing theatre.

Her paintings create a kind of resistance to the erasure of a fragile micro-heritage of coir making communities. She adds mystic overtones by not restricting her world of realism to labour and working- class chores—her visual field has fantastical presences like strangers in dancing poses, masked men etc.

Himanshu Jamod too brings to life the many lives and afterlives of ships—with regenerative processes, in large canvases at Willington Island, in mixed media paintings. Titled Retrieve, the large-scale paintings feature intense colours like yellow, sea green, red, and blue and transform images of wrecked ships into symbols of hope and refuge. His work focuses on the theme of survival; inspired by the lives and work of labourers at the Alang ship-breaking yard of Gujarat.

Jamod works from Vadodara, drawing his memories of growing up in a family of seafarers in Bhavnagar, and the nearby coast of Alang, one of the world’s largest shipbreaking sites, where his relatives worked.

Placed on the large canvases, the merchant ships stand for the self, social body and infrastructure in a flux; as he charts the vessel’s lifespan from the myriad voyages to retirement. These works echo the monumentality and weathered materiality of ships—rendered through painted and printed layers – a palimpsest of nautical and cartographical research.

This year the biennale is larger and more ambitious compared to its previous editions. It is spread across Fort Kochi, Mattancherry, Willington Island and Ernakulam.

True to the title of the biennale, For the time Being, most works are in a state of fluidity; in a state of progress-- evolving with fresh additions and performances. With 66 works and participating artists from 25 countries; for its duration of 110 days, KMB offers myriad experiences around global contemporary art.

By Vandana Shukla